Automatically Detecting AKI Events from Primary Care Records

Introduction

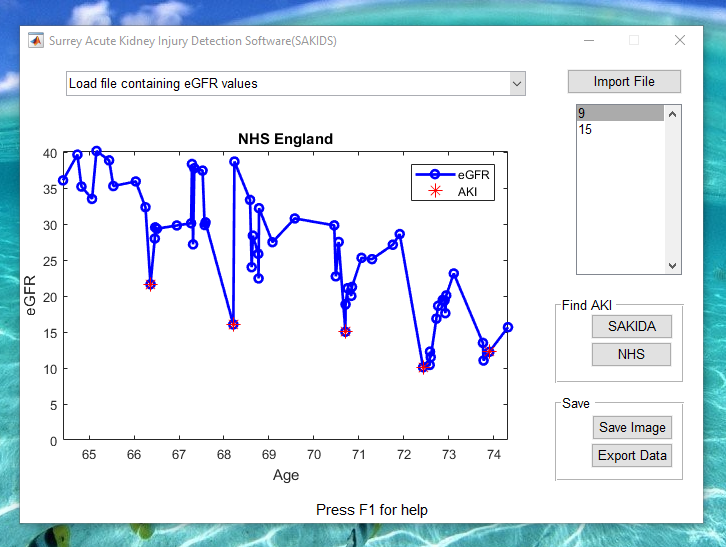

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is characterised by a rapid deterioration in kidney function, and can be identified by examining the rate of change in a patient’s estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Due to the potentially irreversible nature of the damage AKI episodes cause to renal function, their detection can play a significant role in predicting a kidney’s effectiveness. Although algorithms for the detection of AKI are available for patients under constant monitoring, e.g. inpatients, their applicability to primary care settings is less clear as patients’ eGFR often contains large lapses in time between measurements. We therefore present two alternative automated approaches for detecting AKI: using the novel Surrey AKI detection algorithm (SAKIDA) and as the outlier points when using Gaussian process regression (GPR), as shown in the abstract .

Method

The dataset used in this work contains the eGFR data of 488 patients (275 (56.4%) male and 213 (43.6%) female) treated at East Kent University Hospital, and was collected as part of a study seeking to understand the characteristics of acute kidney injury and its impact on chronic kidney disease. Each patient’s eGFR data was manually labelled by a nephrologist with the number of AKI episodes experienced: 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4. In order to obtain the right confidence intervals to detect the AKI episodes as outliers, we trained the GPR using those patients that have no AKI present. The GPR and SAKIDA algorithms were compared to the method developed by NHS England to provide real-time detection and diagnosis of AKI in patients across the National Health Service in England.

Results

SAKIDA was able to identify patients with no AKI episodes with an accuracy of 90.44%, while GPR achieved 83.82% and NHS England 73.53%. SAKIDA also detected no more than 4 AKI episodes per signal, in agreement with the expert’s classifications, while GPR and NHS England detected more in 67 and 99 patients respectively. Interestingly, despite performing worst when detecting 0, 1, 2 and 4 AKI episodes, NHS England method detected eGFR signals with 3 AKI episodes with a greater accuracy than that of the other methods tested (17.64%) (see Table 1).

Conclusion

Unlike the constant monitoring of an inpatient, patients in primary care will likely have less frequent and more irregular eGFR measurements along with a greater variability in eGFR values due to weaker controls over pre-test conditions. The main conclusion that can be drawn from the results is that SAKIDA performs better than both GPR and the NHS England algorithms, not only due to the greater accuracy with which it identifies patients with no AKI episodes, but also because it better matches the expert’s classifications overall. This indicates that GPR and the NHS England algorithms are likely to be less suitable for retrospective identification of AKI episodes in primary care data, and are instead more suitable as real-time alert systems. Given that SAKIDA closely matches the expert’s predictions and can be used for both retrospective analysis and real-time alerts, we believe it should be the method of choice when identifying AKI episodes within primary care data.

What’s next?

- Read the abstract here

- See the poster here

- Play a pre-recorded demo of the SAKIDA software here

- Simply download the SAKIDA software and try it out yourself

- Find our more about the algorithm as published in the 2016 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI)

- Cite the article

@inproceedings{tirunagari2016automatic,

title={Automatic detection of acute kidney injury episodes from primary care data},

author={Tirunagari, Santosh and Bull, Simon C and Vehtari, Aki and Farmer, Christopher and de Lusignan, Simon and Poh, Norman},

booktitle={Computational Intelligence (SSCI), 2016 IEEE Symposium Series on},

pages={1--6},

year={2016},

organization={IEEE}

}Cite this blog post

Bibtex

@misc{ poh_2018_01_13_BRS2017-sakida,

author = {Norman Poh},

title = { Automatically Detecting AKI Events from Primary Care Records },

howpublished = {\url{ http://normanpoh.github.com/blog/2018/01/13/BRS2017-sakida.html},

note = "Accessed: ___TODAY___"

}